big-ip

1341 TopicsBIG-IP for Scalable App Delivery & Security in Hybrid Environments

Scope As enterprises deploy multiple instances of the same applications across diverse infrastructure platforms such as VMware, OpenShift, Nutanix, and public cloud environments and across geographically distributed locations to support redundancy and facilitate seamless migration, they face increasing challenges in ensuring consistent performance, centralized security, and operational visibility. The complexity of managing distributed application traffic, enforcing uniform security policies, and maintaining high availability across hybrid environments introduces significant operational overhead and risk, hindering agility and scalability. F5 BIG-IP Application Delivery and Security address this challenge by providing a unified, policy-driven approach to manage secure workloads across hybrid multi-cloud environments. It can be used to scale up application services on existing infrastructure or with new business models. Introduction This article highlights how F5 BIG-IP deploys identical application workloads across multiple environments. This ensure high availability, seamless traffic management, and consistent performance. By supporting smooth workload transitions and zero-downtime deployments, F5 helps organizations maintain reliable, secure, and scalable applications. From a business perspective, it enhances operational agility, supports growing traffic demands, reduces risk during updates, and ultimately delivers a reliable, secure, and high-performance application experience that meets customer expectations and drives growth. This use case covers a typical enterprise setup with the following environments: VMware (On-Premises) Nutanix (On-Premises) OCP (On-Premises) Google Cloud Platform (GCP) Solution Overview The following video shows how F5 BIG-IP VE running on different virtualized platforms and environments can be configured to scale, secure, and deliver applications equally, even when located on-prem and in cloud environments. By providing a uniform interface and security policies organizations can focus on other priorities and changing business needs. Architecture Overview As illustrated in the diagram, when new application workloads are provisioned across environments such as AWS, GCP, VMware (on-prem), Nutanix (on-prem & VMware) BIG-IP ensures seamless integration with existing services. Platforms Supported Environments VMware On-Prem, GCP, Azure Nutanix On-Prem, AWS, Azure OCP On-Prem, AWS, Azure This article outlines the deployment in VMware platform. For deployment in other platforms like Nutanix and GCP, refer the detailed guide below. F5 Scalable Enterprise Workload Deployments Complete Guide Scalable Enterprise Workload Deployment Across Hybrid Environments Enterprise applications are deployed smoothly across multiple environments to address diverse customer needs. With F5’s advanced Application Delivery and Security features, organizations can ensure consistent performance, high availability, and robust protection across all deployment platforms. F5 provides a unified and secure application experience across cloud, on-premises, and virtualized environments. Workload Distribution Across Environments Workloads are distributed across the following environments: VMware: App A & App B OpenShift: App B Nutanix: App B & App C → VMware: Add App C → OpenShift: Add App A & App C → Nutanix: Add App A Applications being used: A → Juice Shop (Vulnerable web app for security testing) B → DVWA (Damn Vulnerable Web Application) C → Mutillidae Initial Infrastructure & B, Nutanix: App B &C, GCP: App B. VMware In the VMware on-premises environment, Applications A and B are deployed and connected to two separate load balancers. This forms the existing infrastructure. These applications are actively serving user traffic with delivery and security managed by BIG-IP. Web Application Firewall (WAF) is enabled, which will prevent any malicious threats. The corresponding logs can be found under BIG-IP > Security > Event Logs Note: This initial deployment infrastructure has also been implemented on Nutanix and GCP. For the full details, please consult the complete guide here Adding additional workloads To demonstrate BIG-IP’s ability to support evolving enterprise demands, we will introduce new workloads across all environments. This will validate its seamless integration, consistent security enforcement, and support for continuous delivery across hybrid infrastructures. VMware Let us add additional application-3 (mutillidae) to the VMware on-premises environment. Try to access the application through BIG-IP virtual server. Apply the WAF policy to the newly created virtual server, then verify the same by simulating malicious attacks. Nutanix The use case described for VMware is equally applicable and supported when deploying BIG-IP on Nutanix Bare Metal as well as Nutanix on VMware. For demonstration purposes, the Nutanix Community Edition hypervisor is booted as a virtual machine within VMware. Inside this hypervisor, a new virtual machine is created and provisioned using the BIG-IP image downloaded from the F5 Downloads portal. Once the BIG-IP instance is online, an additional VM hosting the application workload is deployed. This application VM is then associated with a BIG-IP virtual server, ensuring that the application remains isolated and protected from direct external exposure. OCP The use case described for VMware is equally applicable and fully supported when deploying BIG-IP with Red Hat OpenShift Container Platform (OCP) including Nutanix and VMware-based infrastructures. For demonstration, OCP is deployed on a virtualized cluster, while BIG-IP is provisioned externally using an image from the F5 Downloads portal. BIG-IP consumes the OpenShift configuration and dynamically creates the required virtual servers, pools, and health monitors. Traffic to the application is routed through BIG-IP, ensuring that the application remains isolated from direct external exposure while benefiting from enterprise-grade traffic management, security enforcement, and observability. GCP (Google Cloud Platform) The use case discussed above for VMware is also applicable and supported when deploying BIG-IP on public cloud platforms such as Azure, AWS, and GCP. For demonstration purposes, GCP is selected as the cloud environment for deploying BIG-IP. Within the same project where the BIG-IP instance is provisioned, an additional virtual machine hosting application workloads is deployed and associated with the BIG-IP virtual server. This setup ensures that the application workloads remain protected behind BIG-IP, preventing direct external exposure. Key Resources: Please refer to the detailed guide below, which outlines the deployment of Nutanix on VMware and GCP, and demonstrates how BIG-IP delivers consistent security, traffic management, and application delivery across hybrid environments. F5 Scalable Enterprise Workload Deployments Complete Guide Conclusion This demonstration clearly illustrates that BIG-IP’s Application Delivery and Security capabilities offer a robust, scalable, and consistent solution across both multi-cloud and on-premises environments. By deploying BIG-IP across diverse platforms, organizations can achieve uniform application security, while maintaining reliable connectivity, strong encryption, and comprehensive protection for both modern and legacy workloads. This unified approach allows businesses to seamlessly scale infrastructure and address evolving user demands without sacrificing performance, availability, or security. With BIG-IP, enterprises can confidently deliver applications with resilience and speed, while maintaining centralized control and policy enforcement across heterogeneous environments. Ultimately, BIG-IP empowers organizations to simplify operations, standardize security, and accelerate digital transformation across any environment. References F5 Application Delivery and Security Platform BIG-IP Data Sheet F5 Hybrid Security Architectures: One WAF Engine, Total Flexibility Distributed Cloud (XC) Github Repo BIG-IP Github Repo 426Views2likes0Comments

426Views2likes0CommentsWhat's new in BIG-IP v21.0?

Introduction In November of 2025 F5 released the latest version of BIG-IP software, v21.0. This release is packed with fixes and new features that enhance the F5 Application Delivery and Security Platform (ADSP). These changes complement the Delivery, Security and Deployment aspects of the ADSP. New SSL Orchestrator Features SNI Preservation SNI (Server Name Indication) Preservation is now supported for Inbound Gateway Mode. This preserves the client’s original SNI information as traffic passes through the reverse proxy, allowing backend TLS servers to access and use this information. This enables accurate application routing and supports security workflows like threat detection and compliance enforcement. Previous software versions required custom iRules to enable this functionality. Note: SNI preservation is enabled by default. However, if you have existing Inbound Gateway Topologies, you must redeploy them for the change to take effect. iRule Control for Service Entry and Return Previously, iRules were only available on the entry (ingress) side, limiting customization to traffic entering the Inspection Service. iRule control is now extended to the return-side traffic of Inspection Services. You can now apply iRules on both sides of an Inspection Service (L2, L3, HTTP). This enhancement provides full control over traffic entering and leaving the Inspection Service, enabling more flexible, powerful, and fine-grained traffic handling. The Services page will now include configuration for iRules on service entry and iRules on service return. A typical use-case for this feature is what we call Header Enrichment. In this case, iRules are used to add headers to the payload before sending it to the Inspection Service. The headers could contain the authenticated username/group membership of the person who initiated the connection. This information can be useful for Inspection Services for either logging, policy enforcement, or both. The benefit of this feature is that the authenticated username/group membership header can be removed from the payload on egress, preventing it from being leaked to origin servers. New Access Policy Manager (APM) Features Expanded Exclusion Support for Locked Client Mode Previously, APM-locked client mode allowed a maximum of 10 exclusions, preventing administrators from adding more than 10 destinations. This limitation has now been removed, and the exclusion list can contain more than 10 entries. OAuth Authorization Server Max Claims Data Support The max claim data size is set to 8kb by default, but a large claim size can lead to excessive memory consumption. You must allocate the right amount of memory dynamically as required based on claims configuration. New Features in BIG-IP v21.0.0 Control Plane Performance and Scalability Improvements The BIG-IP 21.0.0 release introduces significant improvements to the BIG-IP control plane, including better scalability and support for large-scale configurations (up to 1 million objects). This includes MCPD efficiency enhancements and eXtremeDB scale improvements. AI Data Delivery Optimize performance and simplify configuration with new S3 data storage integrations. Use cases include secure ingestion for fine-tuning and batch inference, high-throughput retrieval for RAG and embeddings generation, policy-driven model artifact distribution with observability, and controlled egress with consistent security and compliance. F5 BIG-IP optimizes and secures S3 data ingress and egress for AI workloads. Model Context Protocol (MCP) support for AI traffic Accelerate and scale AI workloads with support for MCP that enables seamless communication between AI models, applications, and data sources. This enhances performance, secures connections, and streamlines deployment for AI workloads. F5 BIG-IP optimizes and secures S3 data ingress and egress for AI workloads. Migrating BIG-IP from Entrust to Alternative Certificate Authorities Entrust is soon to be delisted as a certificate authority by many major browsers. Following a variety of compliance failures with industry standards in recent years, browsers like Google Chrome and Mozilla made their distrust for Entrust certificates public last year. As such, Entrust certificates issued on or after November 12, 2024, are deemed insecure by most browsers. Conclusion Upgrade your BIG-IP to version 21.0 today to take advantage of these fixes and new features that enhance the F5 Application Delivery and Security Platform (ADSP). These changes complement the Delivery, Security and Deployment aspects of the ADSP. Related Content SSL Orchestrator Release Notes BIG-IP Release Notes BLOG F5 BIG-IP v21.0: Control plane, AI data delivery and security enhancements Press Release F5 launches BIG-IP v21.0 Introduction to BIG-IP SSL Orchestrator682Views3likes0CommentsFour Active/Active load balancing examples with F5 BIG-IP and Azure Load Balancer

Background A couple years ago I wrote an article about some practical considerations using Azure Load Balancer. Over time it's been used by customers, so I thought to add a further article that specifically discusses Active/Active load balancing options. I'll use Azure's standard load balancer as an example, but you can apply this to other cloud providers. In fact, the customer I helped most recently with this very question was running in Google Cloud. This article focuses on using standard TCP load balancers in Azure. Why Active/Active? Most customers run 2x BIG-IP's in an Active/Standby cluster on-premises, and it's extremely common to do the same in public cloud. Since simplicity and supportability are key to successful migration projects, often it's best to stick with architectures you know and can support. However, if you are confident in your cloud engineering skills or if you want more than 1x BIG-IP processing traffic, you may consider running them all Active. Of course, if your total throughput for N number of BIG-IP's exceeds the throughput that N-1 can support, the loss of a single VM will leave you with more traffic than the remaining device(s) can handle. I recommend choosing Active/Active only if you're confident in your purpose and skillset. Let's define Active/Active Sometimes this term is used with ambiguity. I'll cover four approaches using Azure load balancer, each slightly different: multiple standalone devices Sync-Only group using Traffic Group None Sync-Failover group using Traffic Group None Sync-Failover group with Failover not configured Each of these will use a standard TCP cloud load balancer. This article does not cover other ways to run multiple Active devices, which I've outlined at the end for completeness. 1. Multiple standalone appliances This is a straightforward approach and an ideal target for cloud architectures. When multiple devices each receive and process traffic independently, the overhead work of disaggregating traffic to spread between the devices can be done by other solutions, like a cloud load balancer. (Other out-of-scope solutions could be ECMP, BGP, DNS load balancing, or gateway load balancers). Scaling out horizontally can be a matter of simple automation and there is no cluster configuration to maintain. The only limit to the number of BIG-IP's will be any limits of the cloud load balancer. The main disadvantage to this approach is the fear of misconfiguration by human operators. Often a customer is not confident that they can configure two separate devices consistently over time. This is why automation for configuration management is ideal. In the real world, it's also a reason customers consider our next approach. 2. Clustering with a sync-only group A Sync-Only device group allows us to sync some configuration data between devices, but not fail over configuration objects in floating traffic groups between devices, as we would in a Sync-Failover group. With this approach, we can sync traffic objects between devices, assign them to Traffic Group None, and both devices will be considered Active. Both devices will process traffic, but changes only need to be made to a single device in the group. In the example pictured above: The 2x BIG-IP devices are in a Sync-Only group called syncGroup /Common partition is not synced between devices /app1 partition is synced between devices the /app1 partition has Traffic Group None selected the /app1 partition has the Sync-Only group syncGroup selected Both devices are Active and will process traffic received on Traffic Group None The disadvantage to this approach is that you can create an invalid configuration by referring to objects that are not synced. For example, if Nodes are created in /Common, they will exist on the device on which they were created, but not on other devices. If a Pool in /app1 then references Nodes from /Common, the resulting configuration will be invalid for devices that do not have these Nodes configured. Another consideration is that an operator must use and understand partitions. Partitions are simple and should be embraced. However, not all customers understand the use of partitions and many prefer to use /Common only, if possible. The main advantage here is that changes only need to be made on a single device, and they will be replicated to other devices (up to 32 devices in a Sync-Only group). The risk of inconsistent configuration due to human error is reduced. Each device has a small green "Active" icon in the top left hand of the console, reminding operators that each device is Active and will process incoming traffic on Traffic Group None. 3. Failover clustering using Traffic Group None Our third approach is very similar to our second approach. However, instead of a Sync-Only group, we will use a Sync-Failover group. A Sync-Failover group will sync all traffic objects in the default /Common partition, allowing us to keep all traffic objects in the default partition and avoid the use of additional partitions. This creates a traditional Active/Standby pair for a failover traffic group, and a Standby device will not respond to data plane traffic. So how do we make this Active/Active? When we create our VIPs in Traffic Group None, all devices will process traffic received on these Virtual Servers. One device will show "Active" and the other "Standby" in their console, but this is only the status for the floating traffic group. We don't need to use the floating traffic group, and by using Traffic Group None we have an Active/Active configuration in terms of traffic flow. The advantage here is similar to the previous example: human operators only need to configure objects in a single device, and all changes are synced between device group members (up to 8 in a Sync-Failover group). Another advantage is that you can use the /Common partition, which was not possible with the previous example. The main disadvantage here is that the console will show the word "Active" and "Standby" on devices, and this can confuse an operator that is familiar only with Active/Standby clusters using traffic groups for failover. While this third approach is a very legitimate approach and technically sound, it's worth considering if your daily operations and support teams have the knowledge to support this. 4. Failover clustering using Failover not configured Finally, my favorite approach: a Sync-Failover group where we simply do not configure any Failover interfaces. This approach has all of our previous advantages: human operators only need to configure a single device all configuration is synced between devices no need to use partitions. All VIPs, pools, nodes, etc can exist in /Common both devices will display the green "Active" we're accustomed to in top-left corner in GUI no need to use Traffic Group None. The only disadvantage here is that while each device will be "green" and Active, if you click into "Devices" and show the peer device, the peer will appear "red" (although it will still be in sync). That's because we have deliberately not configured an IP address for the Failover traffic when we built our cluster. Other considerations Source NAT (SNAT) It is almost always a requirement that you SNAT traffic when using Active/Active architecture, and this especially applies to the public cloud, where our options for other networking tricks are limited. If you have a requirement to see true source IP and need to use multiple devices in Active/Active fashion, consider using Azure or AWS Gateway Load Balancer options. Alternative solutions like NGINX and F5 Distributed Cloud may also be worth considering in high-value, hard-requirement situations. Alternatives to a cloud load balancer This article is not referring to F5 with Azure Gateway Load Balancer, or to F5 with AWS Gateway Load Balancer. Those gateway load balancer solutions are another way for customers to run appliances as multiple standalone devices in the cloud. However, they typically require routing, not proxying the traffic (ie, they don't allow destination NAT, which many customers intend with BIG-IP). This article is also not referring to other ways you might achieve Active/Active architectures, such as DNS-based high availability, or using routing protocols, like BGP or ECMP. Note that using multiple traffic groups to achieve Active/Active BIG-IP's - the traditional approach on-prem or in private cloud - is not practical in public cloud, as briefly outlined below. Failover of traffic groups with Cloud Failover Extension (CFE) One option for Active/Standby high availability of BIG-IP is to use the CFE , which can programmatically update IP addresses and routes in Azure at time of device failure. Since CFE does not support Active/Active scenarios, it is appropriate only for failover of a single traffic group (ie., Active/Standby). Conclusion Thanks for reading! In general I see that Active/Standby solutions work for many customers, but if you are confident in your skills and have a need for Active/Active F5 BIG-IP devices in the cloud, please reach out if you'd like me to walk you through these options and explore any other possibilities. Related articles Practical Considerations using F5 BIG-IP and Azure Load Balancer Deploying F5 BIG-IP with Azure Cross-Region Load Balancer3.4KViews2likes3CommentsWelcome to the F5 BIG-IP Migration Assistant - Now the F5 Journeys App

The older F5 BIG-IP Migration Assistant is deprecated and is replaced by F5 Journeys. Welcome to the F5 Journeys App - BIG-IP Upgrade and Migration Utility F5 Journeys App Readme @ Github What is it? The F5® Journeys BIG-IP upgrade and migration utility is a tool freely distributed by F5 to facilitate migrating BIG-IP configurations between different platforms. F5 Journeys is a downloadable assistant that coordinates the logistics required to migrate a BIG-IP configuration from one BIG-IP instance to another. Why do I need it? JOURNEYS is an application designed to assist F5 Customers with migrating a BIG-IP configuration to a new F5 device and enable new ways of migrating. Supported journeys: Full Config migration - migrating a BIG-IP configuration from any version starting at 11.5.0 to a higher one, including VELOS and rSeries systems. Application Service migration - migrating mission critical Applications and their dependencies to a new AS3 configuration and deploying it to a BIG-IP instance of choice. What does it do? It does a bunch of stuff: Loading UCS or UCS+AS3 source configurations Flagging source configuration feature parity gaps and fixing them with provided built-in solutions Load validation Deployment of the updated configuration to a destination device, including VELOS and rSeries VM tenants Post-migration diagnostics Generating detailed PDF reports at every stage of the journey Full config BIG-IP migrations are supported for software paths according to the following matrix: DEST X 11.x 12.x 13.x 14.x 15.x 16.x <11.5 X X X X^ X^ 12.x X X X X^ SRC 13.x X X X 14.x X X X 15.x X X 16.x How does it work? F5 Journeys App manages the logistics of a configuration migration. The F5 Journeys App either generates or accepts a UCS file from you, prompts you for a destination BIG-IP instance, and manages the migration. The destination BIG-IP instance has a tmsh command that performs the migration from a UCS to a running system. F5 Journeys uses this tmsh command to accomplish the migration using the platform-migrate option (see more details K82540512) . The F5 Journeys App prompts you to enter a source BIG-IP (or upload a UCS file), the master key password, and destination BIG-IP instance. Once the tool obtains this information, it allows you to migrate the source BIG-IP configuration to the destination BIG-IP instance either entirely or in a per-application depending what you choose. Where do I obtain it? F5 Journeys App Readme @ Github What can go wrong? Bug reporting Let us know if something went wrong. By reporting issues, you support development of this project and get a chance of having it fixed soon. Please use bug template available here and attach the journeys.log file from the working directory ( /tmp/journeys by default) Feature requests Ideas for enhancements are welcome here For questions or further discussion please leave your comments below. Enjoy!23KViews3likes38CommentsNew BIG-IP ASM v13 Outlook Web Access (OWA) 2016 Ready Template

F5 has created a specialized ASM template to simplify the configuration process of OWA 2016 with the new version of BIG-IP v13 Click here and download the latest version of XML file that contains the template: Outlook Web Access 2016 Ready Template v6.x Goal: Quick OWA 2016 base line policy which set to Blocking from Day-One tuned to OWA 2016 environment. Ready Template Deployment Steps Download the latest version of the policy XML file (click on the file --> Raw --> Save As) from the link above Update Attack Signature to the latest version: Click "Security Update" --> "Application Security" --> "Check for Updates" --> "Install Updates" Click "Application Security" --> "Import Policy" --> Select File" and choose the XML file Edit the policy name to the protected application name and click "Import Policy" Attach the policy to the appropriate virtual server Refine learning new records in "Application Security" --> "Policy Building" --> Traffic Learning" Observe no false positive occur by validating event logs: "Event Logs" --> "Application" --> "Request" Important: If the policy is not working properly, please ensure you are using the latest version. If you have any issues or questions, please send any feedback to my email: n.ashkenazi@f5.com4KViews0likes25CommentsAccelerate your AI initiatives using F5 VELOS

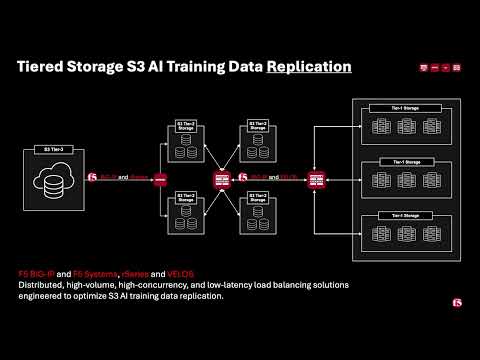

Introduction F5 VELOS is a rearchitected, next-generation hardware platform that scales application delivery performance and automates application services to address many of today’s most critical business challenges. F5 VELOS is a key component of the F5 Application Delivery and Security Platform (ADSP). Demo Video High-Throughput and Concurrency for AI Data Ingestion Given the escalating data demands of AI training and inference pipelines, there is a critical need to architect object-based storage systems, such as S3, and corresponding clients in a manner that ensures high-throughput, scalability, and fault tolerance under massive parallel workloads. S3 Storage Systems increase scalability and resiliency by distributing data objects across multiple storage nodes, leveraging a unified “bucket” abstraction to streamline data organization, access, and fault tolerance. S3 Client Implementations employ highly parallelized, and multi-threaded operations to maximize data transfer rates and throughput, satisfying the low-latency, high-volume requirements of AI and other computationally intensive workloads. Performance and Security for AI Workloads F5 BIG-IP delivers multi-layer load balancing reinforced by robust in-flight security services and performance thresholds engineered to meet or exceed the most demanding enterprise-scale capacity requirements. F5 VELOS Chassis & Blades have advanced FPGA accelerators, high-performance CPU architectures, and cryptographic offload engines. They are all combined with scaling to multi-terabit throughput to meet or exceed the most demanding enterprise capacity requirements. F5 BIG-IP and VELOS enable high-performance data mobility and security for AI workloads anywhere. Load Balancing for S3 AI Training Data Replication Data Replication for Training AI model training and retraining often requires the replication of data from web-service-based object storage tiers to high-performance clustered filesystems. Market Constraints Tier-1 storage systems command high costs, and the ecosystem of certified providers for AI-specific architectures remains comparatively narrow. High-Performance Requirements Effective model training demands access to Tier-1 storage that supports hardware-accelerated data transfers, ensuring rapid delivery of input to GPU memory. S3 Based Migration Replication from cost-efficient, lower-performance storage repositories to Tier 1 infrastructure is commonly orchestrated via the S3 protocol to maintain both scalability and performance. Tiered Storage S3 AI Training Data Replication F5 BIG-IP and F5 Systems, rSeries and VELOS Distributed, high-volume, high-concurrency, and low-latency load balancing solutions engineered to optimize S3 AI training data replication. BIG-IP Best-In-Class Traffic Management & Security: SPEED Smart Load Balancing & Security Directs traffic to the optimal storage for performance, security, and availability. Seamless Data Flow BIG-IP LTM ensures efficient, secure routing from external sources to local storage. Optimized S3 Routing BIG-IP DNS directs client connections to highly available storage nodes for smooth data ingestion. BIG-IP Best-In-Class Traffic Management & Security: SCALE High-Throughput Traffic Management Optimize TCP and HTTPS flows for seamless object storage access. Accelerated Packet Processing Leverage embedded eVPA in FPGA for high-performance L4 IPv4 throughput. Crypto Offload for Speed BIG-IP LTM offloads encryption to best-in-class hardware on rSeries and VELOS, boosting performance. BIG-IP Best-In-Class Traffic Management & Security: Security Robust DDoS Protection BIG-IP’s AFM defends against volumetric and targeted attacks. Secure Traffic Management BIG-IP LTM ensures efficient, secure routing from external sources to local storage. End-to-End Data Protection Safeguards AI workloads with policy-driven security and threat mitigation. F5 Systems Enables Accelerated AI Application Delivery F5 VELOS, rSeries, and BIG-IP Enable distributed, high-volume, high-concurrency, low-latency application delivery for S3. The All-New VELOS CX1610 Provides the multi-terabit throughput necessary for high-performance traffic orchestration. F5 BIG-IP App Services Suite Simplify and secure application delivery for the most demanding high-throughput AI infrastructure needs. Conclusion Unleash Massive Throughput The All-New VELOS BX520 Blade The All-New VELOS CX1610 Chassis Related Articles F5 VELOS: A Next-Generation Fully Automatable Platform F5 rSeries: Next-Generation Fully Automatable Hardware Realtime DoS mitigation with VELOS BX520 Blade 314Views3likes0Comments

314Views3likes0Comments